On Friday (October 7), we had lunch at Los Compadres. Just like last time, Eric ordered their signature lamb tacos. It was tender, shredded meat cooked in spices and served in tortillas. Christi and Keith ordered carne asada tacos, which was tender, shredded steak cooked with just salt and served in tortillas. The tacos were served with platters of accoutrements. Both the tacos and platters looked much the same as we had at La Huastica.

We’d found out that the museum was in a beautiful building that looked like an old plantation, which was on the street above the street that the grocery store was on.

After lunch, we trudged up the multiple flights of steps to the museum. It was a two-story building with high ceilings and a wrap around porch, with views of the town and harbor. Only the first floor was open to the public.

Here is a statue outside the museum

A few of the signs were in both English and Spanish, but most of the signs were only in Spanish. Our Spanish isn’t that good, so there were gaps in comprehension. Just like when she visited the mine museum, Christi left with more questions than she had before going in. Later, Christi looked up information to try to fill in the gaps.

From the sign outside, we gathered that this building was built in 1885 as the administration building for Compania El Boleo, then at some point it became the administration building for Compania Minera Santa Rosalia, which closed down in 1985. Christi was confused – she was certain that the mine was still open.

Christi later found out that El Boleo shut down in 1954. After it closed, Mexican laborers created Minera Santa Rosalia, which continued mining and smelting the ore until the 1960s. After they stopped mining, they continued to smelt ore mined in other countries, apparently until 1985. In 2010, a Korean company began the mining operation again.

The sign also said that the museum was in a perfect state of conservation (hopefully, we translated it correctly). The entrance led into a hallway.

The hallway contained a dual-language sign that gave a brief history of Santa Rosalia. It said that in 1885, the House of Rothschild and Mirabean bank acquired 20,627 hectares of land that would be mined for copper by the newly created Compania El Boleo, which was based in France. Santa Rosalia became the epicenter for the French mining operation.

This answered some of the questions that Christi had after leaving the mining museum. El Boleo had operated many mines in the area, each with its own separate town. She’d wondered if each mine had done its own refining and shipping. The answer was no. All of the ore was transported to Santa Rosalia. The management for all aspects of the mining operations was done from Santa Rosalia.

Since this part of Baja had few natural resources, almost everything necessary to set up the overall mining operation and build each of the mining towns had to be imported from the USA and Europe. Apparently, like the church, the homes for the employees were pre-fabricated kits that were assembled on-site. The sign said the homes were “more like quarters” and “did not respond to the workers physical needs.”

Later, Christi found out that in the early days, each family was given only one bucket of water per day – and they had to pay for it. Waste was also collected daily in buckets, and if the town’s waste pick up was missed, the town reeked. In the winters, the smoke from the chimneys didn’t clear, leading to health issues caused by smoke. And there was no medical care. Eventually, water rations were increased and made free, and medical facilities were built that were also free.

In the hallway, there were also a couple of lithographs. One was the one we’d seen at Terco’s of the aerial tram system. Christi later found out that the aerial tram had been built in the 1930s. It was the first funicular system in Latin America. The other lithograph was of what the town of Santa Rosalia looked like at the time. It wasn’t dated, but we assume both lithographs were produced about the same time.

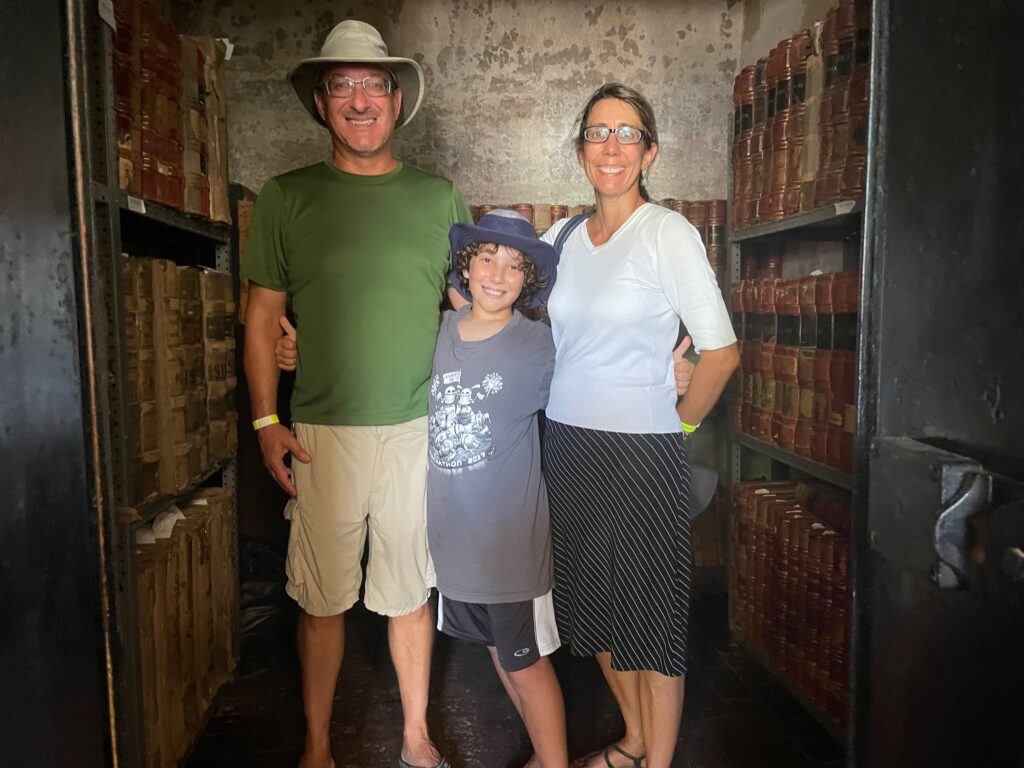

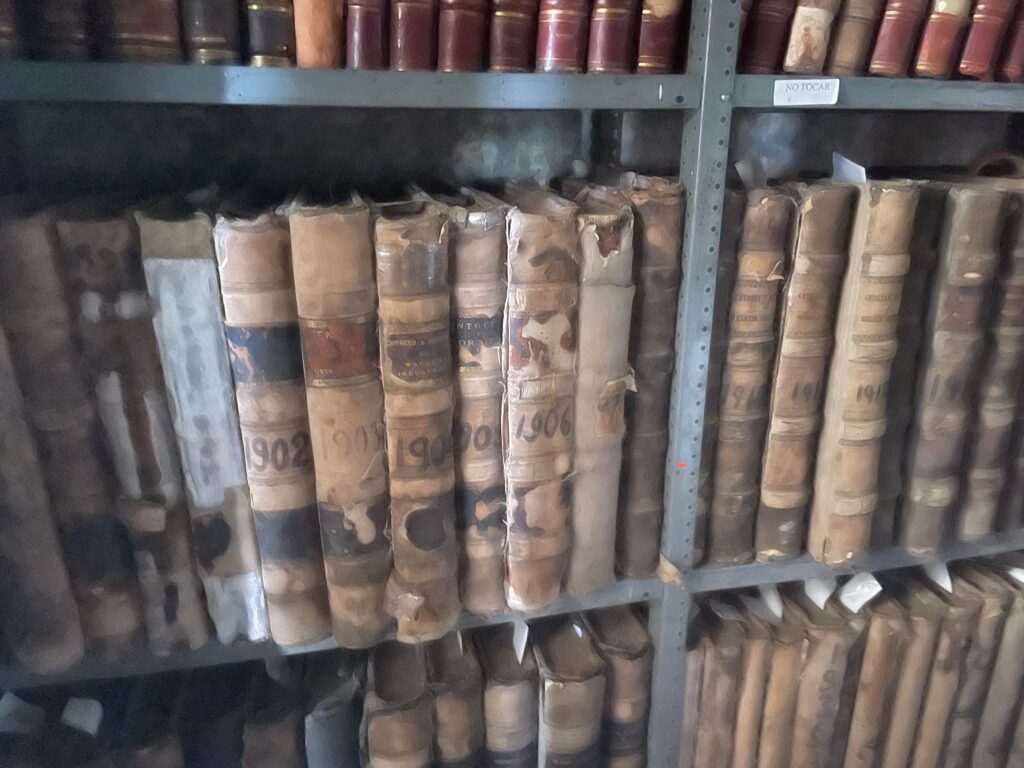

The first room to the left contained old records. Most were stored in a vault. The first photo is us standing in the vault, the second are some of the ledgers.

That room led into another room, which contained tools used in the company’s operations.

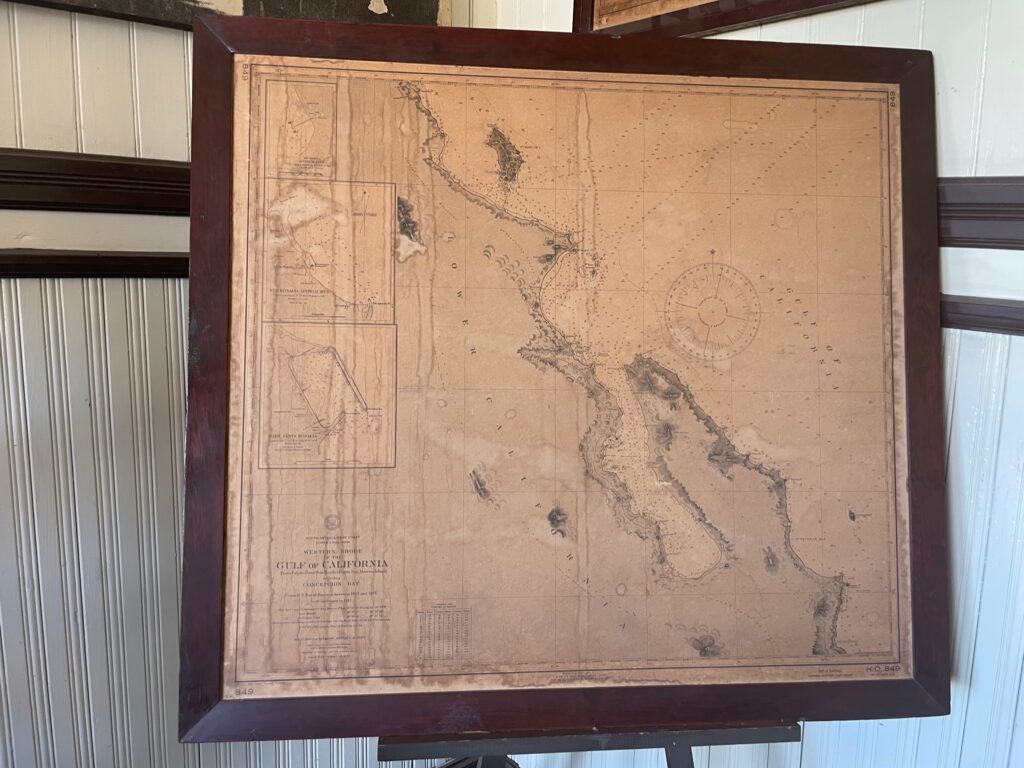

That led into another room that had information about the fleet of ships that were part of their operations. Christi found out later that the construction of the sea wall was completed in 1922, and there were three docks that could accommodate six large ships at a time. Here is an old map that we found interesting.

This room led back into the hallway. In the photo of the hallway above, you can see there was a room at the end of the hallway. It was a conference room.

Across the hall was a room full of sports memorabilia.

That led into a large room with desks with various office machines, such as a telephone switchboard, mimeograph, accounting machine, cash register, etc.

As far as we could tell, there wasn’t much information about the infrastructure. There was actually more information about the infrastructure at the mine museum. Christi later found out that In addition to the railroad system, refinery, and port, El Boleo had also built an electric power plant. Santa Rosalia was the second city in Mexico to be electrified (the first was Mexico City).

Christi walked along the street that the museum was on. Both sides of the street had historic buildings and there was old railway equipment in the median and along the cul-de-sac.

Christi later found out that back in the day, this street had been dubbed Mesa Francia, and it was where El Boleo’s directors had lived. At the end of the street was a hotel, which Christi found out had originally been built as a hotel for the visiting overseas businessmen.

To be continued…

Santa Rosalia looks really pretty! Love the old museum books and equipment. I’m a fan of old mines too (taken quite a few tours in various SW mines…not sure what’s so appealing about being underground in the dark but it’s a very unnatural and weird feeling!)